Nuclear and present danger

MIT security experts discuss how to lower tensions between the U.S. and North Korea.

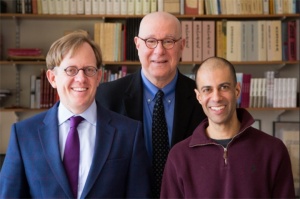

Left to right: Vipin Narang, associate professor of political science and a member of the Security Studies Program; Jim Walsh, senior research associate at the Security Studies Program; and Taylor Fravel, associate professor of political science, a member of the Security Studies Program, and acting director of the MIT Center for International Studies.

Photo: Courtesy MIT Center for International Studies

Rising tensions between the U.S. and North Korea have an unsettling chance of escalating, MIT security experts said at a public forum on Tuesday — but are also manageable given the right approach by U.S. leaders.

“I think you can get inadvertent war,” said Jim Walsh, a senior research associate in MIT’s Security Studies Program (SSP) and a nuclear security expert who has visited North Korea in the past. “It’s still an unlikely event,” he added. However, he also stated, “I would remind you that improbable events do happen. … I am more worried than I have been before.”

To keep the situation under control, the panel of three nuclear-security scholars said, the U.S. would do well to seek further diplomatic talks with North Korea. The U.S. should also reconcile itself to the fact that North Korea does have nuclear weapons and, for a variety of reasons, it must not expect China to address the situation decisively.

“We should certainly be talking to them,” said Walsh, who, like others on the panel, believes that North Korea’s nuclear capacity is almost certainly here to stay.

“The bad news is that denuclearization is a fantasy,” said Vipin Narang, an associate professor of political science at MIT, who has written extensively about North Korea’s nuclear program and gave a summary of the country’s current capabilities. “The good news is, deterrence can work.”

Meanwhile China — who some U.S. leaders, including President Donald J. Trump, have sometimes cited as a key actor in this scenario, given its political alignment with North Korea — seems unwilling to play a larger role in the current state of affairs.

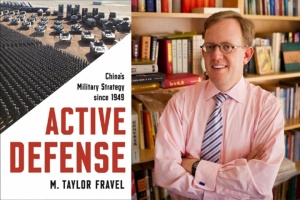

“I think China believes that the North Koreans are developing nuclear weapons for perfectly [logical] reasons,” said Taylor Fravel, an associate professor of political science at MIT and interim director of MIT’s Center for International Studies (CIS). Fravel, a leading expert on China’s foreign-policy conflicts, added that Chinese leaders, who maintain their own nuclear arsenal, likely view North Korea’s weapons as “an insurance policy, one they [China] can see in their own history.”

The event drew a crowd of at least 225 people, packing a lecture hall in MIT’s Building 34. The three panelists all delivered prepared remarks and responded to a series of audience questions. The discussion was part of the CIS Starr Forum, a series of public discussions on world politics.

North Korea: New arsenal, familiar strategy

Narang gave the audience an overview of which types of missiles and nuclear payloads North Korea has developed, based on the best public knowledge available. North Korean leader Kim Jong Un has publicly announced a lengthy series of tests over the course of 2017.

“He acquired nuclear weapons to avoid a U.S.-led regime change,” Narang said, adding that the North Korean strategy is “risky, but it’s not irrational.”

Indeed, Narang emphasized, the North Korean nuclear strategy is precisely the same one used by Pakistan and, to a large degree, NATO forces during the Cold War. North Korea has seemingly developed short-range missiles capable of delivering nuclear bombs, and as of this summer, an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) capable of reaching North America.

Both types of missiles are necessary for North Korea to achieve a kind of mutual deterrence with the U.S., Narang pointed out. That is, if North Korea only had shorter-range missiles and used them to deliver a nuclear bomb in, for instance, a conflict with South Korea, then South Korea’s allies — namely, the U.S. — could respond by essentially wiping out North Korea in retaliation.

However, the presence of North Korean ICBMs that could deliver nuclear weapons to North America stands as a deterrent to such a U.S. reply, hypothetically.

“That’s why the ICBM is so important” to North Korea, Narang pointed out, adding that North Korea can now “put the U.S. homeland at risk.”

On the other hand, Narang pointed out, the U.S. has experience and know-how at maintaining forms of equilibrium among nuclear powers with the same sets of capabilities — not only the former Soviet Union and Russia, but more recently, Pakistan, among other cases.

So: What should be done?

That leaves open the matter of what the U.S. should be doing, specifically. For starters, Narang said, “We need to tighten our message and be consistent and coherent.”

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Secretary of Defense James Mattis, he pointed out, have both publicly stated that regime change in North Korea is not a U.S. goal. According to the terms of nuclear logic, that should settle the situation somewhat. However, Trump has used more belligerent language, both in a recent speech at the United Nations and in his Twitter messages.

“Why would Kim think we might attack him? Because we keep saying that over and over again,” Walsh said.

Additionally, Narang stated, the U.S. should almost certainly not attempt a military attack on North Korean military sites in an attempt to eliminate its weapons program, due partly to the extreme difficulty of identifying and hitting every relevant site.

“Denuclearization by force is a very risky proposition and it’s not an experiment we want to run,” Narang said.

Walsh added that he was “not a big believer that sanctions are going to solve this problem,” given North Korea’s current capabilities, and Fravel emphasized that China is also not likely to be interested in having regime change occur in North Korea. Among other reaons, he noted, “the collapse of any more communist countries would be a great concern for China.”

Instead, Walsh and Narang concluded, further talks with North Korea might help limit the extent of North Korea’s arsenal and reduce the possibility that U.S.-led military exercises around the Korean peninsula could trigger a military incident that escalates to nuclear use — which, the scholars observed, seems by far the most likely route to a catastrophic exchange between the countries.

“Giving up on denuclearization doesn’t mean you give up on nonproliferation,” Narang said.

However, observers have concerns about many types of things that could unsettle the situation in North Korea. Scott Sagan, a Stanford University professor and leading nuclear-security expert who was in the audience for the event, pointed out during the question-and-answer period that false news reports circulated last weekend, stating that the U.S. was advising nonessential personnel to depart the Korean peninsula. That kind of report, Sagan noted, could be mistakenly interpreted as a prelude to military action.

“I’m worried about this, even though I think it is unlikely,” Sagan said. And, as Walsh added, “Certain leaders in the world pay more attention to news reports than to their advisors.”

With so many unresolved issues at stake, Walsh said, “That uncertainty makes me nervous, and gnaws at me.”