By some lights, it seems curious how authoritarian leaders can sustain their public support while limiting liberties for citizens. Yes, it can be hard to overthrow an entrenched leader; that does not mean people have to like their ruling autocrats. And yet, many do.

After all, authoritarian China consistently polls better on measures of trust and confidence in government than many democratic countries, including the U.S. And elected leaders from Africa to East Asia and Europe have seen their popularity rise after rolling back civil rights recently. What explains this phenomenon?

“Successful authoritarians do not take public support and the durability of their systems for granted,” says MIT political scientist Lily Tsai, who has spent years studying autocratic regimes. “They know they have to constantly work hard to make sure there is support and voluntary cooperation.”

The specific way many autocrats achieve this, Tsai believes, is by investing heavily in “retributive justice,” the high-profile use of punishment against people who have run afoul of values shared by leaders and their supporters. Such punishments, it seems, signal to the public that its leaders are maintaining a social order based upon core moral values, even as they restrict certain liberties.

“It’s an important strategy for mobilizing public support that unfortunately we don’t always acknowledge,” Tsai says. “Successful authoritarians understand that people need to feel there is a stable social and moral order, arguably before anything else, and they have to consciously and continuously produce it.”

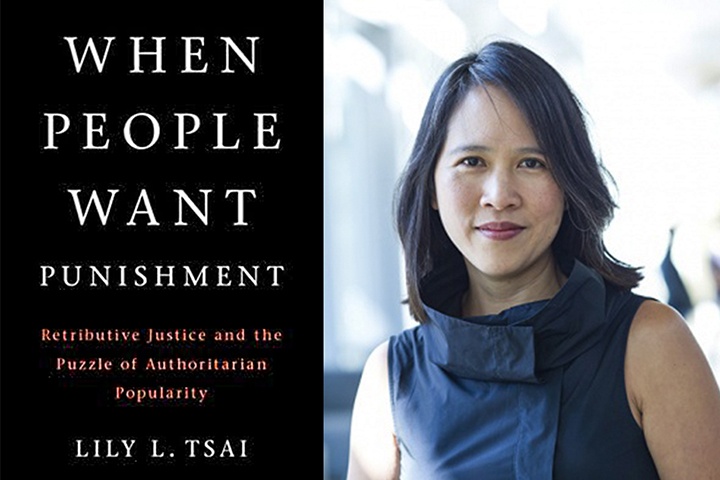

Now Tsai, the Ford Professor of Political Science and chair of the MIT faculty, has examined this idea at length a new book, “When People Want Punishment,” published by Cambridge University Press. In it, she explores how retributive justice functions, and seeks to shift our understanding of how authoritarians prosper — an especially urgent question while many have gained traction around the globe.

The overlooked “foundation of any stable political system”

As Tsai observes, there are multiple kinds of justice that citizens expect from governments. Distributive justice is the allocation of material goods. Procedural justice is the impartial application of the rule of law. And retributive justice, as Tsai says, is “the just allocation of punishment when there is wrongdoing.” However, she adds, “retributive justice is not revenge, which is an emotional reaction to a wrong that’s been done, and often violent.”

In a high-functioning democracy, retributive justice appears as the normal legal process. In other countries, it takes other forms. In the Philippines, it has been made manifest through the government’s campaign against criminality and drugs. In China, where Tsai conducted fieldwork for the book, retributive justice is evident in the national government’s long-running anticorruption campaigns that punish local officials, often severely.

Through a variety of empirical means, including sophisticated public-opinion research in rural and urban China, Tsai has established that the Chinese public has a strong interest in public anticorruption campaigns — even in the absence of evidence that those campaigns reduce corruption. Being publicly against corruption helps political figures at moments of economic struggle; as an issue, Chinese citizens rank anticorruption efforts alongside welfare measures and administering elections fairly.

Indeed, popular anticorruption campaigns against local officials are such a persistent part of politics in China that, in Tsai’s interpretation, the presence of local corruption is virtually by design. Local officials have many unfunded mandates, and often seem to have to choose between failing in their jobs or finding dubious means of accomplishing their goals.

“It’s very hard [for local officials] not to be breaking some rules at some point,” Tsai says. “This is very useful for the Chinese [federal] state because it allows them to always position local officials as the bad guys. They can always be the good guys and punish the local officials. It’s a robust system of maintaining public support.” Of China’s national government, she adds, “They have made both the production of the moral order and the production of threats to that order a mainstay of their approach to governance.”

All told, Tsai writes, “retributive justice is one of the most important and perhaps the most fundamental public good that a government provides to its citizens.” And in contrast to what other scholars have concluded, Tsai contends that retributive justice is virtually the key to state-building, because without civic order, distributive and procedural justice cannot operate.

“Retributive justice is the foundation of any stable political system, but we just don’t think about it that way,” Tsai says.

Commitment to a common project

Tsai’s analysis of retributive justice represents a shift in thinking about authoritarian regimes. Many scholars have focused on elite sources of support for autocrats, such as business, the military, and more. But sometimes authoritarians survive not only through coercion and repression. When they gain public support, Tsai believes, we need to understand that process better.

“I think those of us who are committed to liberal democracy often find it difficult to see the strength of these authoritarian regimes,” Tsai says. And, realistically, she notes, some portion of people in a given country “would rather just live and have a livelihood” than suffer the risks of fighting for more freedom.

Other political scientists have lauded Tsai’s new book. Anthony Saich, a professor of international affairs and director of the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at the Harvard Kennedy School, has called it a “brilliant study” that “resonates far beyond China to help explain why even in established democracies there can be a yearning for a strong ruler who will set wrongs to right.”

For her part, Tsai hopes the book will be read by anyone with an interest in state-building, democracy-building, and simply understanding the current trends toward illiberal authoritarianism.

“People in international development are typically thinking about the need to get government to provide basic public services, health care and clean water and education, but one of the most important and basic public goods governments need to provide is moral order and social stability,” Tsai says. “That is not something that has always been articulated before.”

And while supporters of democracy might feel “allergic” to learning lessons about authoritarian popularity, those dynamics are important to grasp, Tsai says — not in order to imitate them, but to understand how democratic countries can also provide a sense of order and stability.

“Until you have that, promoting democracy really doesn’t have the salutary effects that we think it will have,” Tsai says. “You need a functioning state that can uphold the social order first. … The foundation for a commitment to a common project has to be laid from the very beginning.”

Reprinted with permission of MIT News.