3 Questions: Chappell Lawson on U.S. security policy

New book, “Beyond 9/11,” explores the country’s multifaceted security needs in the 21st century.

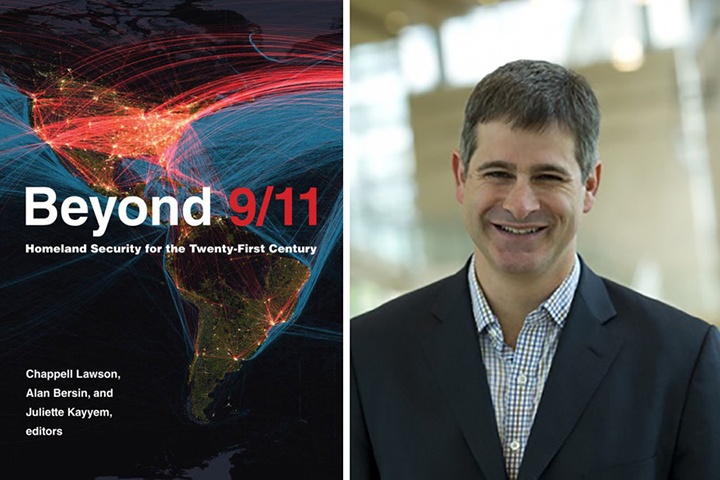

MIT Associate Professor Chappell Lawson is co-editor of a new book, “Beyond 9/11: Homeland Security for the Twenty-First Century,” published by MIT Press.

Photo: Stuart Darsch

The year 2020 has featured an array of safety and security concerns for ordinary Americans, including disease and natural disasters. How can the U.S. government best protect its citizens? That is the focus of a new scholarly book with practical aims, “Beyond 9/11: Homeland Security for the Twenty-First Century,” published by the MIT Press. The volume features chapters written by 19 security experts, and closely examines the role of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which was created after the September 2001 terrorist attacks on the U.S.

The book is co-edited by Chappell Lawson, an associate professor of political science at MIT, who has served at DHS as executive director of policy and planning, and senior advisor to the commissioner, U.S. Customs and Border Protection. His two co-editors are Juliette Kayyem, faculty director of the Homeland Security Project at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at the Harvard Kennedy School, who was previously an assistant secretary for Intergovernmental Affairs at DHS; and Alan Bersin, Inaugural Fellow at the Belfer Center’s Homeland Security project, who was previously Commissioner of U.S. Customs and Border Protection, and later head of policy at DHS. MIT News talked with Lawson about the book.

Q: If homeland security is moving “beyond 9/11,” as the book puts it, what does that entail?

A: It’s hard to imagine a functioning government without homeland security, which means protecting the country from nonmilitary threats: responding to global pandemics, managing borders, counterespionage, and protecting critical infrastructure from cyber attacks. It’s also hard to imagine these things being done without the federal government. The aspiration is to do them more efficiently and coherently.

The 9/11 terrorist attacks crystallized a particular notion of homeland security. But that focus on counterterrorism obscured almost everything else. Hurricane Katrina was a course correction, highlighting the fact that many other threats deserved attention. More recently the issue of cyber threats against critical insfrastructure, including election infrastructure, raises a whole new set of challenges, and Covid-19 has highlighted the importance of preventing and addressing deadly pandemics. All of those are homeland security issues, and the effort the government puts into them has to be proportional and balanced.

Q: Okay, speaking of balance, what’s the right balance of power between the federal government and states? The book explores this, and we can grasp — for instance — that there are clear benefits to distributing election oversight among states, counties, and even towns. But it might be harder for those smaller administrative entities to accumulate the cybersecurity knowledge they need to protect elections.

A: It’s a mess. When it comes to immigration, it’s clear the federal government has the leading role. But there are places where the roles themselves are not clear, including management of pandemics and cybersecurity. So, nobody’s solved the issue of homeland security in a federal structure. For instance, the Constitution allocates responsibility for election administration to the states, and the states then decentralize further. Yet it’s very clear that a breakdown in one or two particular counties in swing states could disrupt the entire system. If a determined adversary were trying to accomplish this goal, with relatively modest and focused effort they could call into question the legitimacy of the entire system. And that makes it a homeland security issue. We haven’t sorted that out yet.

We wrote this book imagining how to improve the homeland security enterprise. The analogy is Berlin in 1990: You could look at the city and see some blighted areas and some beautiful areas that showed what the city might be 30 years later, the gleaming capital that Berlin is today. The book is providing a roadmap for getting from Berlin in 1990 to Berlin in 2020. But we can also see from earlier history that without proper oversight, there are real dangers of politicization.

Congressional oversight is cluttered and capricious — fragmented among different committees. I think there’s a consensus that oversight should be streamlined. Of course, every congressional committee would like to streamline oversight in its own hands. Still, there are plenty of people on Capitol Hill who care about homeland security being executed properly, so there should be an opportunity to create better oversight.

Q: What have you learned about security issues from the Covid-19 pandemic?

A: I think everything we predicted about homeland security was borne out in the context of the pandemic. If the right relationships are not built between the federal government, the states, civil society, and the private sector, you will reap a very poor harvest.

A slightly different revelation from Covid-19 is that homeland security has distributional consequences. We’re used to thinking of homeland security as what economists call a pure public good [enjoyed equally by all], but some people suffer more from the measures that are needed to secure all of society. In the pandemic, the self-employed and the hospitality sector, among others, have borne the brunt of social distancing measures. That’s something the whole homeland security apparatus has not wrestled with yet: Society as a whole can be better off, but some are doing so much better than others, that we’re inadverdently recapitulating the inequality in society. That’s a good lesson for other disasters.

Reprinted with permission of MIT News