The intersection of technology and war

MIT excels in teaching the science and technology associated with the operation of societies, businesses, and militaries, says Fiona Cunningham PhD ’19.

“I chose MIT because no other political science graduate program had such strengths in both East Asia and security studies,” says Fiona Cunningham PhD ’19. “I want to understand the changing nature of warfare and how new technologies have become both opportunities and restraints for countries in international politics.”

Fiona Cunningham/Center for International Studies

Pursuing big questions is part of the MIT ethos, says Fiona Cunningham PhD ’19.

“Walking through the Infinite Corridor, you can see what people are doing in this space. There is such dedication across the Institute to solving big problems. There is dedication to doing the best work, without hubris, and often without a break. I find this so exciting, and it’s a huge part of what makes me so proud to be an alumna. This dedication will stay with me forever.”

Cunningham completed her PhD at the Department of Political Science, where she was also a member of the Security Studies Program. Her work explores how technology affects warfare in the post-Cold War era. She studies how nations — China specifically — plan to use technology in conflict to achieve their aims.

“I want to understand the changing nature of warfare and how new technologies have become both opportunities and restraints for countries in international politics. These questions are the kinds of questions that global leaders are thinking about when they are grappling with the rise of China, how technology factors into the current U.S.-China trade war, and how technology does or doesn’t fit within national boundaries.”

She received the Lucian Pye Award for outstanding PhD thesis. The award was established by the political science department in 2005 and recipients are determined by the graduate studies committee. Pye was a leading China scholar who taught political science at MIT for 35 years.

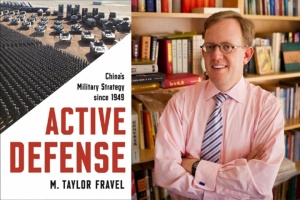

"Fiona’s thesis was exemplary. She asked an important question that bears on the future of peace and stability among nations, and conducted an impressive amount of original research about a topic that is especially challenging to study. In this way, she combined academic rigor with policy relevance,” says Taylor Fravel, the Arthur and Ruth Sloan Professor of Political Science and director of the MIT Security Studies Program.

The road to China

Cunningham was born and raised in Australia, where the influences of neighboring East Asia are strong. This is what led to her initial curiosity about the region. After high school, she took a gap year and spent part of it in China, where she was drawn into the culture and politics — and the challenge of learning Chinese.

She returned to Australia for her undergraduate studies and recalls two pivotal experiences that guided her academic path: a visiting semester at Harvard University, where she got a taste for the U.S. approach to studying international relations, and working as a research associate at the Lowy Institute for International Policy, an Australian think tank. There she worked with Rory Medcalf, whose early attention to the international security challenges created by the rise of China really helped shape her research questions, says Cunningham.

After those experiences, she knew what she wanted to study and she knew she wanted to study at MIT.

“I chose MIT because no other political science graduate program had such strengths in both East Asia and security studies. And, as someone who has always been interested in science and technology and its impact on international politics, the idea that I would be at an Institute where so much brain power is dedicated to advancing the scientific and technological aspects of how our societies, businesses, and militaries operate was amazing!”

A model community

The Department of Political Science and the Security Studies Program provided a thriving community for Cunningham.

The faculty and scholars she worked with —Taylor Fravel, Vipin Narang, Barry Posen, Owen Coté, Frank Gavin — are models of how to do rigorous scholarship about the things that really matter for the way our world works, she says: “They somehow contribute fully to the discipline and the public debate, which is both super-human and very inspiring.”

Fravel served as her dissertation chair. “Taylor was my mentor, my professor, and, in addition to that, my co-author. I was so fortunate to be able to learn how to think, research, write, and teach from him in all of those roles.”

Fravel and Cunningham co-authored a paper in 2015 on China’s nuclear strategy. They have a forthcoming paper delving further into that topic that examines China’s views of nuclear escalation.

Three women — Lena Andrews ’18, Marika Landau-Wells ’18, and Ketian Zhang ’19 — went through the program with Cunningham. “We really helped each other and we will always have a special bond.”

The support she found in these relationships, plus her family, has been a source of inspiration. “My parents have always encouraged me to do something I was passionate about, do it really well, and to do something that will make a difference,” she says.

Breaking new ground

Cunningham joined George Washington University as assistant professor of political science and international affairs this fall after completing a postdoctoral fellowship at the Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford University.

She chose an academic track because she wants the freedom to continue to pursue the international relations questions she finds most important.

It is also her strong ambition to continue doing fieldwork, especially within China.

“I want to see the problems I research through the eyes of people on the front lines. In addition to my fieldwork in China, the Security Studies Program provided me with these kinds of experiences through field trips to U.S. military bases during graduate school. You can’t get that from a book.”

She also looks forward to teaching. “For me, teaching is about teaching students how to think critically about future problems, and how to write and communicate their analysis and their thinking.”

Cunningham had the opportunity to serve as a teaching assistant in undergraduate courses while at MIT. “The students at MIT are so capable. They would bring their STEM background to topics like cybersecurity and the causes of war. I would walk away amazed! If these students are our future, then our world will be good hands.”

As a professor, she aims to help her students consider the consequences, both intended and unintended, of employing technology. She wants them to think about the political questions that come into play both now and into the future.

MIT really gets you attuned to this crossover of technology and its social and political implications, she explains.

The San Francisco (California) Bay Area, where she has spent the last year, provided fertile ground for her to dig deeper.

“Silicon Valley is the innovation engine of the U.S. economy, and arguably the world economy. I've been looking around there to see what are the next political science questions. What is the next big question that sits at the intersection of technology and conflict? And what role does great power competition play in the day-to-day life of tech companies? What is the role of individuals and the companies they are running in making decisions that have big political implications?”

Pursuing big questions is a part of Cunningham’s ethos. This dedication will stay with her forever.